Dearest beautiful boy,

It must be strange to receive a letter from your prospective human parents, seeing that you’re barely a few weeks after two months and you’re not yet aware of what’s going to happen. All you know is that you’re with your brothers and your mom and dad, playing and suckling on milk, not knowing that the life you’re set is to be ripped away from them and be a poster boy for Stockholm Syndrome.

I joke, but, well.

I am writing to you, because, reflecting on it now, when your mum and I chose you, we had the option. This was the decision: we told ourselves we’d get the middle child. How we decided on that was, once your original human owners opened the dog crate, we’d pick the second one to come out. There were three of you then remaining in the litter, and we thought, the first one to come out would be the obviously rowdy one. The last one would be the meek, potentially weakling one.

We wanted the middle so that we thought we could get the best of both worlds—a good mix of personality, if you will. It was you who stepped out after your frisky little brother, followed after maybe a good 10 seconds by your third, rather frail-looking brother. You were definitely not the runt of the litter, and while we may be biased, maybe you’re the best-looking one of them, too.

You never had the decision. You were chosen and then you had to simply be.

My dearest little Charley, I’m letting you know what life you would have should you decide to be with us:

You would live to be eleven years, four months, twelve days. You would leave us at 10:50 a.m. You would die of cardiac arrest.

I’m getting ahead, and I wish that’s the only pain I can promise you would get. But if you choose to be with us, little one, there are many more ahead of you:

At two years old, you would fly with your mum to another country, Singapore, a 3-hour flight that would put you in a crate. You would be placed in a quarantine area alone and afraid, and I would only get to meet you 24 hours later, where you would howl-cry in relief when you hear my distinct whistle. It would teach you perhaps the first hard lesson on what it means to be you: that there are going to be days you’ll be alone. And most of them, while you’re in pain.

Your mum and I would spend a lot of time trying to undo those things, but they would stay with you. We know, because you can’t seem to leave our side, always worried about being left alone. And we’d spend our life trying to make you feel safe and loved, but sometimes we’re not sure if you ever understood what those moments mean, that being left alone for a bit would mean we would all be together again.

You would also damage both of your knees at the young age of six. First your right leg, then after a few weeks, your left. The doctor would claim that it’s in your DNA, but for a time, your mum and I would blame ourselves, thinking maybe because we’ve been playing you too much or too strong. You would have those painful surgeries and would have to be carried most of the time especially when it gets too painful after long walks. You would have a love-hate relationship with backpacks that carry you on hikes, but you’d have a first love in the blue pram your mum thoughtfully bought for you.

You would have a long constant painful relationship with doctors, so much so that you shiver in fright whenever you see the vet. There would be at least one injection shot per month for you for close to 7 years–that’s approximately 80 injections minimum, 50+ of those I had to do for you just so you don’t have to see the vet for that month.

You would also have to bear another flight, again, alone, at age 10. This time it would be for a 9-hour flight to New Zealand, where your mum and I hoped to be where our little family would take root. Unlike the last time, we would only get to meet you after 10 days in quarantine, and while you would show relief, you would later on whine and never let us leave your sight for weeks after, worried that we would leave you alone again.

And just months before your death, you would even get in an accident where a big dog would bite a chunk of your neck. You would go in for surgery alone and when you come back to us, the three of us would be sleeping together on the sofa because we couldn’t move you and you wouldn’t settle unless you were sure we were both on each of your side.

These are the unfortunates that would come with choosing us, and you may have to think hard if having those pains would be worth it. I cannot guarantee that choosing different parents may mean less pain, but at least somehow you would know what you’re signing up for.

–

There would be a lot of good moments, as I would like to imagine.

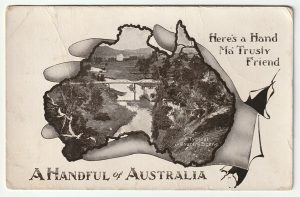

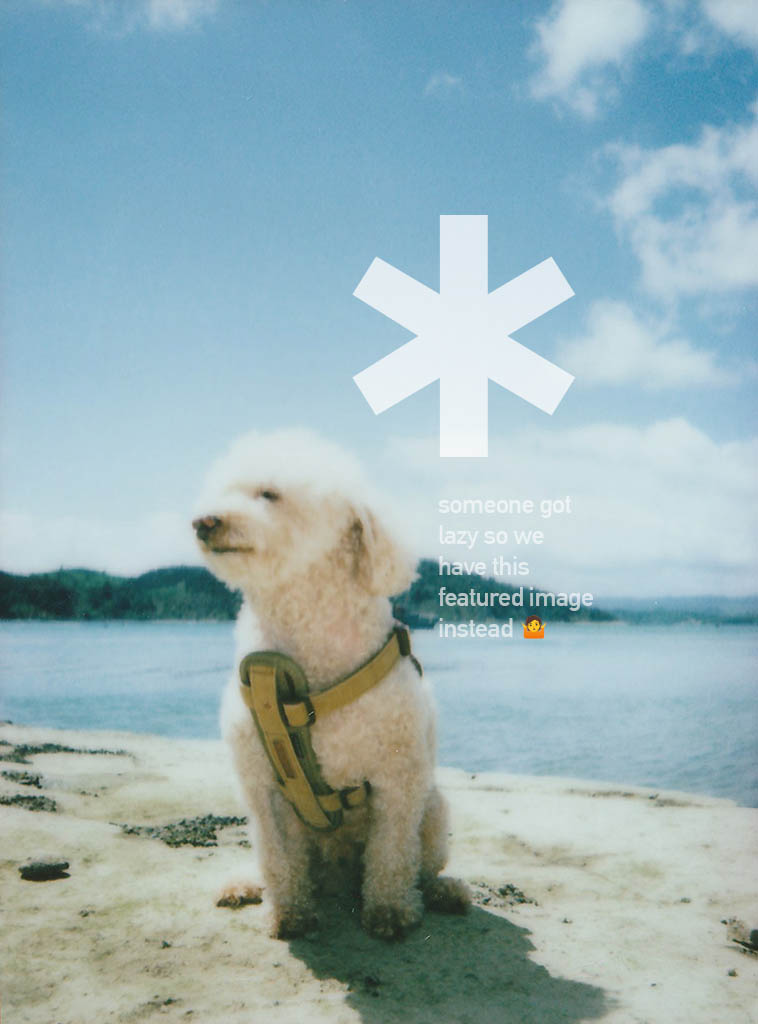

You would come to adore the beach. Unfortunately not the waters, but running, digging, burrowing in, and being lightly covered under the sand delights you. We would find that out in the Philippines when that one time we first brought you to this white beach in Subic you just wouldn’t stop digging and eating sand. You would also develop a taste for good places, because that one time I tried bringing you to a beach near your grandma’s place you disliked it with passion because the sand’s black and dirty. You would get that trait from your mum, apparently. We would bring you to the beach whenever we could, and when we got to New Zealand we made it a mission to bring you to as many different beaches as possible. Within a year we would get to visit at least 20 different beaches around and near Auckland, aside from doing quick getaways to the beach 5 minutes away from our place on Tuesdays or Thursdays when I’m working from home.

We would also go on other adventures, putting up with my ideas but never backing out of a challenge. In the span of eleven years, you would have tried kayaking, paddle-boarding, swimming, hiking, biking, longboarding, running, basketball guard, and tennis ball fetcher. The one you enjoyed the most seemed to be biking after we bought you a dog seat fitted into my foldable bike, and we clocked maybe about 200 kms on that thing, just biking around and loving the wind on your face despite having fallen on that bike together twice (strangely, while parked–because I am an absolute klutz and I am so, so sorry).

You would also love going out to pubs. Your nose would wiggle like crazy whenever we would pass by them, and even if we didn’t really have plans to, your mum and I would drink a pint just so we could get fries for you. You’d just sit there and watch humans around you and wait patiently for any bar food passed on to you. You’d later switch to coffee shops when you get to NZ, and you would just like the idea of sitting on chairs, as long as you can see what’s on the table.

You would like hikes and fields and long rides, and you would get especially excited by vacations because we would try as much as we could to bring you to pet-friendly hotels. You would get excited when you would find new hotels. The one you would love the most was Capella Singapore, where you would explore wide-eyed, and you would jump around as if the room was booked specifically for you. And then there’s another cabin over at Raurimu, where you just pretended like we booked the whole cabin for you as you ran around inspecting the place happily (spoiler alert, Nix–one of the families you’d have when you get to New Zealand–did, in fact, book the cabin for you).

You would also be loved by almost every single person you encounter. You would be living a life where everyone who would meet you would fall in love with you, and while you would be fiercely protective of each of them, they would be doting and loving of you in return. It’s not something that shouldn’t be an issue, but it’s something everyone would have to contend with once you finally leave.

Apparently, loving you meant having to bear the pain of losing you, but from what I would gather, everyone wouldn’t have it any other way.

—

You would live to be eleven years, four months, twelve days. You would leave us on October 25th, at 10:50 a.m., 10 minutes after your critical care doctor would give up on you. I know because she would tell us before it happens. And we would cry, burdened by the weight of the decision to carry the fact that there’s absolutely nothing else we could do. Your body, despite the amount of personality and soul you bring to everyone, was simply not enough to sustain you. Your organs were failing, she would say. It would be merciful to no longer resuscitate you because you would be living a short life in pain. It may be minutes or hours before another potential cardiac arrest takes you, and it might not be worth it anymore just for us to see you one more time.

She would call to give us that news a few minutes after 10 a.m. We would get ready to see you one last time–the third of “one last time” we would be doing for the past 24 hours since you got admitted to the emergency / ICU. She would call again at around 10:30 to tell us that you’re going into cardiac arrest, and they would try to resuscitate you for 10 minutes, but anything beyond that would be merciless and futile.

You would leave while we’re 5 minutes away, and I would take that call while we’re on Auckland Bridge, trying to rush that car ride to get to you. But you’re gone. You would not wait for us anymore.

You would leave us on a good day. For once in a long downcast string of days that week in Auckland, that Wednesday would be bright and sunny, one of those perfect days where we could have walked to your favourite coffee shop to grab anything just so you’d feel you’d had your coffee run.

You would leave us on a good day, but you would leave us in pain, too.

—

What you won’t experience, dear little one, but I think you may need to know once you decide to be with us, are the following:

You would leave us on a good day that simply did not mirror the pain of everything. That Wednesday would leave us in this purgatory of having sunshine while the doctor called us to say you have passed when were 5 minutes away, would be one of the worst feelings we would have to deal with. We would start calling our offices to say we have to deal with the death of a family, but they wouldn’t fully understand how losing a dog would mean losing a family.

To them you’re a dog; to us, you’re our only son.

The doctors would begin to tell us there wasn’t anything we could have done. You would have a degenerative mitral valve disease that, while the doctors in Singapore would tell us you might have had more time, the doctors in NZ would tell us your heart has grown, and it triggered water in your lungs that it often placed you in a delicate situation.

The night before you leave us, your mum and I would be sitting on the bedroom floor, hating ourselves for not having enough money to cover whatever potential surgery you could have needed before this happened or any potential hospital care you needed beyond this. We would hate our incapability to provide for you while we mulled the option with one of the doctors to consider DNR or euthanasia when that next one happens, only for the doctors to tell us that your condition has progressed way too far that having to prolong your life may mean pain for you.

We would hold on to that guilt, anger, and pain, Charley. I would spend some time hating myself for every single thing I could have missed. For every bit that the doctor said, or what I could have countered or bartered with the universe against. I would hate my self for some time, and your mum would try to convince me it wasn’t my fault while she herself would be parsing through so much anger and loss. She would be grieving with me but she would try to help me when she could; what she wouldn’t know is that I know she’s crying in the other room. She wouldn’t know I was breaking down in front of your pictures, or while I hugged the bunny toy you held while you spent your last nights in the ICU.

I would scream at the universe for not allowing me to be there 24/7 on those days you go to hospitals alone, just because you’re a dog and vets work differently in this world. I would get haunted by the last look on your face as we said goodbye, your small neck craning to support your head as you looked at me, afraid and longing, while I couldn’t do anything. Because leaving you in the hands of someone more capable meant bargaining with the gods for another day with you hopefully. And that’s constantly going to be the theme of the life you’d choose with us–that every time you think you’re left alone we’d carry the guilt of not being able to explain that it means we’re temporarily leaving you in the capable hands of doctors and pilots and pet movers, in hopes that doing that gamble means we’d get to spend more time with you.

But you were just my small boy who wouldn’t be able to fully understand, and in exchange, you’d constantly be anxious and worried that we’d leave you, even if everything we would do would be to make sure you live a longer life with us.

Every day I wish I could explain that to you as you would look at me from the ICU, wondering why we’re leaving you alone again in that operating bed.

We would finally get the call that your cremated remains are ready. I would have a hard time reconciling that my 6kg+ baby boy–the same son I have carried for eleven years, four months, and twelve days, could simply fit in a small box not bigger than my hand.

—

I am telling you these things because you need to know that this is what comes with loving you. It comes with so much happiness we can’t even fathom, but at the same time, it comes with so much pain, guilt, and anger. But please understand, that as I am writing this letter, we are still grieving you. And I am angry at the world for not being able to afford me more days with you.

Please don’t ever think loving you is something we’d ever regret, if anything, we feel that eleven years, four months, and twelve days are never enough.

I am telling you all these, negative or semi-positive as they may seem, because every single bit of this makes you, you.

You would feel them in your bones, every single day molding you to be the dog you would become with us. And I know you don’t have many ideas of how that’s going to look, but from how everyone’s missing you now–me and your mother especially–you were absolutely adored and definitely loved.

They are, for us, every single thing that would make you smell like what you do at 10 p.m. when I kiss you between your eyes every night. They are, from what I gather, what’s composed of the longing I would have every single day until the day I finally meet you again in the afterlife.

So please, do us the honour of choosing us in this lifetime.

Yours truly,

Your mom.